Enter the Woods: Finding My Trees, And the Mother Trees Part Two

The Copper Beech of my childhood home was where I discovered my quiet place within.

Scared and brave, I climbed higher than my bedroom window.

Straddled on a branch, not moving, I bent my head to watch

clouds. When my mother called, I didn't answer.*

In motherhood, with my daughters on their own, I planned a house sale with one sad decision. Leaves were dropping from a yellow maple tree in the front yard, and a large branch perfect for a child's swing appeared ready to break. Stationed in a lawn chair, I watched as the crew began dropping the sawn branches. When I casually turned my head toward the neighbor's woods, I was surprised to see the aura of those trees wavering between their topmost branches and the blue sky. My sadness shifted to encompass their seeming grief, or possibly their good-bye. I felt grateful we were there to witness.

Thirteen years later, I built a home in India in a field where only a few others lived at a distance. Inside my tall brick wall, I planted a six-foot neem tree in view of the window above the kitchen sink. One morning, as I was slowly washing dishes and gazing at the young neem tree, I spontaneously said—"Trees are my friends"—my voice surprising me. Why had it taken me so long to recognize this? I remembered how as a budding poet in my thirties, I had written a poem about my childhood love of trees.

Beneath a tree-umbrella

a girl rides a raft

of roots, dirt-cool

idly rubbing the bark.

Years later, I now knew why I had been comforted by trees all my life.

Suzanne Simard, author of Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest explores mothering in the world of trees—by older ones for the younger growing nearby. She grew up in a family that made its living cutting down forests. At age twenty, on a seasonal job for a logging company in western Canada, she was assigned to assess established plantations of seedlings put in to replace harvested trees. Forestry school had taught her that "trees only compete with one another to survive,"* but what she realized later was that in this ecosystem, trees and plants seem "to need one another for survival."*

Simard discovered, to her surprise, that the forest has trees that are "ancient giants. . . . social beings that exchange nutrients, help one another, and communicate to others."* She named them "the Mother Trees" and made a commitment to take their discovery to global awareness.

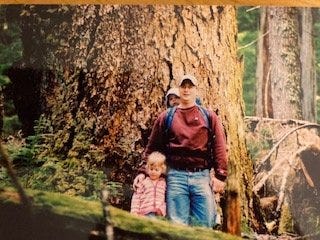

"Go find a tree—your tree," Simard encourages her readers. "Imagine linking into her network, connecting to other trees nearby. Open your senses."* My chosen tree is nearby. She is old with a big girth. I've set a chair near her for visiting. To date, I've stopped several times, only leaning my back against her, for now, and just for moments . . . then having closed my eyes, inwardly I speak to her.

My realization is, "A shift in how we see trees, from being useful for shade, protection, producing crops, providing building material, or offering beauty may expand to a personal relationship that we could name 'in friendship,' or even 'as mothering.'"

* Prema Jasmine Camp, A Flower for God: A Memoir (Seattle, WA: Wilson Duke Press, 2021), 40.

* Camp, 44.

* Suzanne Simard, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forrest (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2021), 50.

* Simard, 50.

* Richard Schiffman, "'Mother Trees’ Are Intelligent: They Learn and Remember,” Scientific American, May 4, 2021, para 2, https:// www.scientificamerican.com/article/mother-trees-are-intelligent-they learn-and-remember.

* Simard, 305.