My days of bhaji (vegetable) shopping are done. I made that decision following a daunting experience of buying vegetables, followed by several months of thinking that my effort was still a pleasure, then finally facing that I was seventy-four and needed to prioritize the use of my energy.

In my early years of residence, I had bought my vegetables by taking a Trust* bus to town, then walking into the bazaar. The cavernous, old brick building had sellers both outside and inside. I regularly went in through a turnstile in the front following the one time that I had gone in the back. I had thought that it would be quicker because it was closer. It was. But the narrow, pounded-dirt path was made even narrower by my being uncomfortably crowded by two cows, and the air was unpleasantly smelly from the stinging odor of public toilets, an odor that wrinkled my nose.

In my early years of residence, I had bought my vegetables by taking a Trust* bus to town, then walking into the bazaar. The cavernous, old brick building had sellers both outside and inside. I regularly went in through a turnstile in the front following the one time that I had gone in the back. I had thought that it would be quicker because it was closer. It was. But the narrow, pounded-dirt path was made even narrower by my being uncomfortably crowded by two cows, and the air was unpleasantly smelly from the stinging odor of public toilets, an odor that wrinkled my nose.

Once through the front turnstile, it was a lengthy walk (about thirty feet) to the seller that I liked. What I remember of the in-between space is that at first view, it looked like a low (two foot) wall about thirty feet long and fifteen feet that led across to a walkway from a second front entrance. I didn’t understand what purpose this area had until many years later, when one day I went in the other front entrance. On my walk to the center area where wide and open side entrances brought foot traffic into the building, I happened to glance to the right just to the place where a stone in that low wall had been moved, revealing storage space below—I had a glimpse of vegetables. Now I understood. Of course there needed to be a cool, dark storage area for more vegetables than were on display.

Once through the front turnstile, it was a lengthy walk (about thirty feet) to the seller that I liked. What I remember of the in-between space is that at first view, it looked like a low (two foot) wall about thirty feet long and fifteen feet that led across to a walkway from a second front entrance. I didn’t understand what purpose this area had until many years later, when one day I went in the other front entrance. On my walk to the center area where wide and open side entrances brought foot traffic into the building, I happened to glance to the right just to the place where a stone in that low wall had been moved, revealing storage space below—I had a glimpse of vegetables. Now I understood. Of course there needed to be a cool, dark storage area for more vegetables than were on display.

The building was unclean, remarked on only because I came from America where I regularly shopped in bright-light clean supermarkets—but also outdoor stands. The light was dim, every feature dwarfed by a distant pitched roof. However, I had been told that this was where to come. So, gradually growing accustomed to this new adventure, I shifted my focus. Each seller’s stand was well-manned and the sellers helpful. The shoppers gave it an air of vibrancy—and me an unforgettable experience. There were six medium-sized, sloping platforms where sellers on higher boards could view the crowded shoppers (it was always crowded no matter what time I went) as well as the width of their spread of vegetables. Those that I could identify were carrot, okra, pumpkin, cauliflower, beet, half-green tomatoes, string beans, sweet potato, cucumber, and bottle gourd. There was rarely an English speaker—only those of Marathi and Hindi so I could not question. Both sellers and shoppers (mainly ladies) were industrious but only the shoppers were gregarious; the sellers stayed fixed on sales. In a group clustered about a front edge created by horizontal, shallow bins of vegetables, I decided on my choices then kept my eyes on the seller until I was noticed. “Kiti paise?” (How much?) I asked, as my plastic bags were handed down.

The building was unclean, remarked on only because I came from America where I regularly shopped in bright-light clean supermarkets—but also outdoor stands. The light was dim, every feature dwarfed by a distant pitched roof. However, I had been told that this was where to come. So, gradually growing accustomed to this new adventure, I shifted my focus. Each seller’s stand was well-manned and the sellers helpful. The shoppers gave it an air of vibrancy—and me an unforgettable experience. There were six medium-sized, sloping platforms where sellers on higher boards could view the crowded shoppers (it was always crowded no matter what time I went) as well as the width of their spread of vegetables. Those that I could identify were carrot, okra, pumpkin, cauliflower, beet, half-green tomatoes, string beans, sweet potato, cucumber, and bottle gourd. There was rarely an English speaker—only those of Marathi and Hindi so I could not question. Both sellers and shoppers (mainly ladies) were industrious but only the shoppers were gregarious; the sellers stayed fixed on sales. In a group clustered about a front edge created by horizontal, shallow bins of vegetables, I decided on my choices then kept my eyes on the seller until I was noticed. “Kiti paise?” (How much?) I asked, as my plastic bags were handed down.

Learning from a friend that he took a six-seater or larger rickshaw to town, I ventured off to try one. For five rupees, I could go whenever I wanted. I became comfortable squeezed in with both men and women, children sitting on laps, sleeping babies, and shuffling my feet around the shopping bags that increased or vanished as people got in or out. Often I climbed over the back panel for one of the four side-facing spaces. I was accepted and felt one with the villagers in their lifestyle, as they knew that I had a choice.

When after three years, I was able to buy land to build a home I purchased a car, a nine-year-old Maruti (that I still drive eight years later). With a few minor but scary accidents, I learned to drive in local traffic where there are few rules and drivers who obey none. It was harrowing. However, I rationalized that this was brain stimulation and followed my own basic precautions.

After living in my home for five years, I changed my routine and took a private rickshaw to town, and this continued until my regular driver retired. At that point, he told me of a local market only ten minutes away. On my first exploration, I found the correct lane where I could see sellers seated on the ground. Driving slowly, enveloped by shoppers, I stole one-second glances left and right looking for carrots and okra, the purpose of my trip. At the end of the lane where the market continued to the left, I turned and found that I was now in a driving-hell situation. Fearing hitting someone, I crept along, moving my eyes to see in front, in back, and on both sides. Daunted by not knowing how to get out of this, I finally pulled into an opening and just sat, unable to follow even the thought that I needed to get out and ask for help. Minutes went by. Finally in my side mirror, I noticed a man looking my way. Apparently he had figured out my situation. He came to my passenger window (I drive on the right), bent down and smiled across at me with the reassurance that I badly needed. Then with one hand he motioned me to begin backing up (and he may have kept the other resting on the car—at least it felt as if he was controlling the car). Judging that I was apprehensive, or lacked skill, he kept up his directions until I was safely in the road and facing in the right direction. During the several months that I returned, I parked on the main road and walked in. But that first afternoon I had proved my skill—handling a six-point turn.

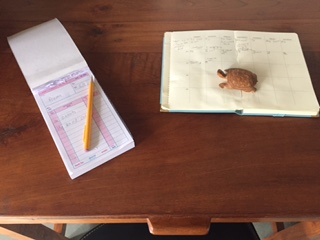

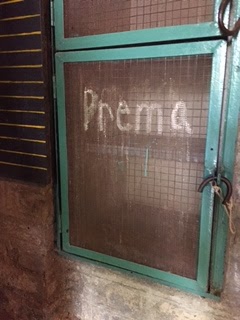

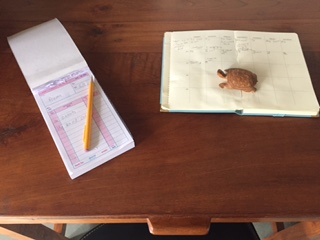

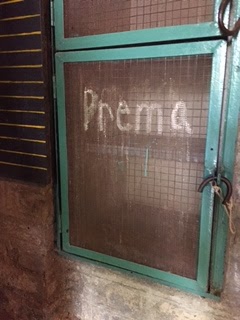

For the past year I have had a bazaar shopper, a man who shops for the kitchens and other residents, buying more than food if needed. I write out my order at my kitchen desk and take a copy to add to other slips on a spindle in a small community building housing a kitchen and dining area. I pay the shopper in advance, usually a thousand rupees, which at the current rate is about sixteen USD. The next day my order is in my pinjra.

My realization is, “Independence is a valuable characteristic when appropriately adjusted for age and ability. It can, at times, be taken too far when, in fact, surrender to being helped is simply another kind of independence—that of wisdom.”

* personal storage space, with the /j/ pronounced as a /z/.

* The Avatar Meher Baba Perpetual Public Charitable Trust. www.ambppct.org

In my early years of residence, I had bought my vegetables by taking a Trust* bus to town, then walking into the bazaar. The cavernous, old brick building had sellers both outside and inside. I regularly went in through a turnstile in the front following the one time that I had gone in the back. I had thought that it would be quicker because it was closer. It was. But the narrow, pounded-dirt path was made even narrower by my being uncomfortably crowded by two cows, and the air was unpleasantly smelly from the stinging odor of public toilets, an odor that wrinkled my nose.

In my early years of residence, I had bought my vegetables by taking a Trust* bus to town, then walking into the bazaar. The cavernous, old brick building had sellers both outside and inside. I regularly went in through a turnstile in the front following the one time that I had gone in the back. I had thought that it would be quicker because it was closer. It was. But the narrow, pounded-dirt path was made even narrower by my being uncomfortably crowded by two cows, and the air was unpleasantly smelly from the stinging odor of public toilets, an odor that wrinkled my nose.

Once through the front turnstile, it was a lengthy walk (about thirty feet) to the seller that I liked. What I remember of the in-between space is that at first view, it looked like a low (two foot) wall about thirty feet long and fifteen feet that led across to a walkway from a second front entrance. I didn’t understand what purpose this area had until many years later, when one day I went in the other front entrance. On my walk to the center area where wide and open side entrances brought foot traffic into the building, I happened to glance to the right just to the place where a stone in that low wall had been moved, revealing storage space below—I had a glimpse of vegetables. Now I understood. Of course there needed to be a cool, dark storage area for more vegetables than were on display.

Once through the front turnstile, it was a lengthy walk (about thirty feet) to the seller that I liked. What I remember of the in-between space is that at first view, it looked like a low (two foot) wall about thirty feet long and fifteen feet that led across to a walkway from a second front entrance. I didn’t understand what purpose this area had until many years later, when one day I went in the other front entrance. On my walk to the center area where wide and open side entrances brought foot traffic into the building, I happened to glance to the right just to the place where a stone in that low wall had been moved, revealing storage space below—I had a glimpse of vegetables. Now I understood. Of course there needed to be a cool, dark storage area for more vegetables than were on display.

The building was unclean, remarked on only because I came from America where I regularly shopped in bright-light clean supermarkets—but also outdoor stands. The light was dim, every feature dwarfed by a distant pitched roof. However, I had been told that this was where to come. So, gradually growing accustomed to this new adventure, I shifted my focus. Each seller’s stand was well-manned and the sellers helpful. The shoppers gave it an air of vibrancy—and me an unforgettable experience. There were six medium-sized, sloping platforms where sellers on higher boards could view the crowded shoppers (it was always crowded no matter what time I went) as well as the width of their spread of vegetables. Those that I could identify were carrot, okra, pumpkin, cauliflower, beet, half-green tomatoes, string beans, sweet potato, cucumber, and bottle gourd. There was rarely an English speaker—only those of Marathi and Hindi so I could not question. Both sellers and shoppers (mainly ladies) were industrious but only the shoppers were gregarious; the sellers stayed fixed on sales. In a group clustered about a front edge created by horizontal, shallow bins of vegetables, I decided on my choices then kept my eyes on the seller until I was noticed. “Kiti paise?” (How much?) I asked, as my plastic bags were handed down.

The building was unclean, remarked on only because I came from America where I regularly shopped in bright-light clean supermarkets—but also outdoor stands. The light was dim, every feature dwarfed by a distant pitched roof. However, I had been told that this was where to come. So, gradually growing accustomed to this new adventure, I shifted my focus. Each seller’s stand was well-manned and the sellers helpful. The shoppers gave it an air of vibrancy—and me an unforgettable experience. There were six medium-sized, sloping platforms where sellers on higher boards could view the crowded shoppers (it was always crowded no matter what time I went) as well as the width of their spread of vegetables. Those that I could identify were carrot, okra, pumpkin, cauliflower, beet, half-green tomatoes, string beans, sweet potato, cucumber, and bottle gourd. There was rarely an English speaker—only those of Marathi and Hindi so I could not question. Both sellers and shoppers (mainly ladies) were industrious but only the shoppers were gregarious; the sellers stayed fixed on sales. In a group clustered about a front edge created by horizontal, shallow bins of vegetables, I decided on my choices then kept my eyes on the seller until I was noticed. “Kiti paise?” (How much?) I asked, as my plastic bags were handed down. Learning from a friend that he took a six-seater or larger rickshaw to town, I ventured off to try one. For five rupees, I could go whenever I wanted. I became comfortable squeezed in with both men and women, children sitting on laps, sleeping babies, and shuffling my feet around the shopping bags that increased or vanished as people got in or out. Often I climbed over the back panel for one of the four side-facing spaces. I was accepted and felt one with the villagers in their lifestyle, as they knew that I had a choice.

When after three years, I was able to buy land to build a home I purchased a car, a nine-year-old Maruti (that I still drive eight years later). With a few minor but scary accidents, I learned to drive in local traffic where there are few rules and drivers who obey none. It was harrowing. However, I rationalized that this was brain stimulation and followed my own basic precautions.

After living in my home for five years, I changed my routine and took a private rickshaw to town, and this continued until my regular driver retired. At that point, he told me of a local market only ten minutes away. On my first exploration, I found the correct lane where I could see sellers seated on the ground. Driving slowly, enveloped by shoppers, I stole one-second glances left and right looking for carrots and okra, the purpose of my trip. At the end of the lane where the market continued to the left, I turned and found that I was now in a driving-hell situation. Fearing hitting someone, I crept along, moving my eyes to see in front, in back, and on both sides. Daunted by not knowing how to get out of this, I finally pulled into an opening and just sat, unable to follow even the thought that I needed to get out and ask for help. Minutes went by. Finally in my side mirror, I noticed a man looking my way. Apparently he had figured out my situation. He came to my passenger window (I drive on the right), bent down and smiled across at me with the reassurance that I badly needed. Then with one hand he motioned me to begin backing up (and he may have kept the other resting on the car—at least it felt as if he was controlling the car). Judging that I was apprehensive, or lacked skill, he kept up his directions until I was safely in the road and facing in the right direction. During the several months that I returned, I parked on the main road and walked in. But that first afternoon I had proved my skill—handling a six-point turn.

For the past year I have had a bazaar shopper, a man who shops for the kitchens and other residents, buying more than food if needed. I write out my order at my kitchen desk and take a copy to add to other slips on a spindle in a small community building housing a kitchen and dining area. I pay the shopper in advance, usually a thousand rupees, which at the current rate is about sixteen USD. The next day my order is in my pinjra.

My realization is, “Independence is a valuable characteristic when appropriately adjusted for age and ability. It can, at times, be taken too far when, in fact, surrender to being helped is simply another kind of independence—that of wisdom.”

* personal storage space, with the /j/ pronounced as a /z/.

* The Avatar Meher Baba Perpetual Public Charitable Trust. www.ambppct.org